|

March 5, 2008

The mystery of mammoth tusks with iron fillings

By By Ned Rozell A giant meteor may have exploded over Alaska thousands of years ago, shooting out metal fragments like buckshot, some of which embedded in the tusks of woolly mammoths and the horns of bison. Simultaneously, a large chunk of the meteor hit Alaska south of Allakaket, sending up a dust cloud that blacked out the sun over the entire state and surrounding areas, killing most of the life in the area.

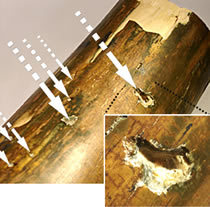

Embedded iron particles surrounded by carbonized rings in the outer layer of a mammoth tusk from Alaska. Inset photo shows how an object ripped through the tusk. Image courtesy Richard Firestone.

Such is the scenario envisioned by Rick Firestone, a staff scientist at

the

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. Firestone and his

colleagues have found mammoth tusks and a bison skull with nickel-rich

iron

particles in them on one side, suggesting the metal fragments all came

from

the same direction.

Firestone's theory emerged when his colleague, Alan West of Dewey,

Arizona,

saw at a Phoenix gem and mineral show a mammoth tusk peppered with tiny

bits

of metal. Intrigued, West and Firestone looked at tusks owned by the

same

dealer in Calgary. By passing a magnet over mammoth tusks in Calgary,

Firestone and West found seven mammoth tusks collected somewhere near

the

Yukon River and a bison skull from Siberia that had tiny iron fragments

burned into them. The fragments also contained nickel.

"One in 1,000 tusks had this material in it," Firestone said.

Firestone also thinks he may have found the divot left by the ancient

meteorite, an impact crater that is now occupied by a round body of

water

named Sithylemenkat Lake in the upper Kanuti River drainage.

"The creeks coming out of the lake are very rich in nickel," Firestone

said,

referring to a metal associated with meteorites. "And the shape is

consistent with a crater from a meteorite that may have been a half a

kilometer in diameter

A meteorite that big would have torched anything within a 100-mile

radius

and could have buried the mammoths farther away from the crater,

preserving

the tusks struck by metal fragments. Firestone said the dust kicked up

by

the meteor would have eliminated any mammoths that survived the

meteor's

hit.

"There was probably 10,000 years with no mammoths," he said, adding

that

other mammoths eventually migrated back into Alaska.

Dale Guthrie, one of Alaska's few experts on mammoths, said he found

Firestone's theory interesting, but Alaska scientists who know about

impact

craters think he is probably off on his guess that Sithylemenkat Lake

is the

place where a giant meteorite struck about 35,000 years ago (the

approximate

age of the mammoth tusks). Scientists have confirmed only one impact

crater

in Alaska

Buck Sharpton, an expert on impact craters and the Vice Chancellor for

Research at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said the lake would

have to

be much older than 35,000 years because it has no rim associated with

more

recent impact craters and doesn't look to him like an impact crater. He

thinks the iron bits in the tusks could be cavities filled by "being

immersed for millennia in porous sedimentary fill through which

iron-rich

water percolated."

As for Sithylemenkat Lake, Gordon Herreid didn't mention a possible

meteorite impact when he wrote a 1969 geology report on the lake for

the

state (which ordered the investigation because of possible nickel

deposits

there). Jan Cannon wrote in the journal Science in 1977 that the lake

looked

to be the only visible impact crater in Alaska based on a study of

Landsat

satellite images. One year later, William Patton of the U.S. Geological

Survey argued in Science that glaciers, rather than a meteorite,

created the

lake.

© AlaskaReport News

This column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.

|

|