|

Alaska's Megaproject Mentality - Part 2March 10, 2007Courtesy of insurgent 49

The Rampart Dam The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers first proposed the massive Rampart Dam project in the early 1950s, but the idea really picked up speed immediately after statehood. The plan was to dam the Yukon at Rampart Canyon, near the town of Rampart. The only tangible long-term benefit of the dam, other than having the reputation of being monumentally huge, was to generate electricity. If it had been built, the Rampart Dam at the time would have become the world's largest hydroelectric plant, with about 5,000 megawatts (MW) of electric generation capacity. Just to give some perspective on how much electric power that is, the present-day electric generation capacity entire state of Alaska is just over 2,000 MW. Since only about 220,000 people lived in Alaska during the early 1960s, some really "creative" ideas were dreamt up to use all of the electricity. Optimistic schemes were dreamt up to find a use for all of that electric power, in order to make Alaska into an instant industrial subcontinent by using the dam megaproject to spawn many son-of-megaprojects. The dam-boosters boasted that the Alaskan wilderness would "blossom" with world's largest aluminum smelters, steel mills, and any other industry that would want a whole lot of cheap, federally-subsidized electricity.

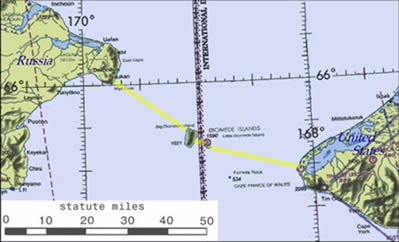

Partly modeled after large federal dams such as those of the Columbia River, the Rampart Dam project was pushed heavily by Alaska's then-U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening. It was just a side note to the dam-boosters that backing up a stream as big as the Yukon River would have created a 10,850 square mile reservoir, to be over 400 miles long and up to 80 miles wide. This artificial lake would have been so large that it would have taken almost 30 years to fill up completely. More than a quarter million salmon pass through Rampart Canyon each year, and millions of ducks make their homes in the wetlands of the Yukon flats. About 1500 people would have been directly displaced by the huge reservoir, and the lives of thousands more would be negatively impacted by the loss of fish and animal life, but Gruening didn't care. Gruening visited the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, and the huge dams that he saw there made him jealous. In hindsight, we can be glad that the Yukon River didn't end up like the Volga River, as today the reservoirs of the Volga are among the most toxic and polluted in the world. With high-level political support, two "grassroots" pro-dam activist groups were formed: Yukon Power for America and the North of the Range Association. Both of these short-lived organizations had an eerie similarity to the pseudo-grassroots political pressure groups that exist in present-day Alaska such as the oil industry front group Alaska's Future. By the mid-1960s, the Rampart project got tied up in the ongoing rivalry between the Army Corps and the U.S. Department of the Interior's Bureau of Reclamation (BuRec) over which of the two federal agencies could build the biggest and the most dams, losing sight of whether the structures were actually needed. Around the same time as the Rampart proposal, a multi-dam hydroelectric project on the Susitna River was being proposed by BuRec, strategically located between Anchorage and Fairbanks. The Susitna project, while still large enough to be considered a megaproject, was far more realistic in terms of scale to the actual energy needs of the state. BuRec, and the rest of the Department of the Interior, turned against the Rampart Dam, and the project was dead by the early 1970s. By the late 1970s, BuRec had dropped its proposed multi-dam project Susitna River, and the state of Alaska started to study building the Susitna hydroelectric project by itself. A multibillion-dollar, two-dam version of the Susitna project would have consisted of power plants at Watana (1020 MW) and Devil Canyon (600 MW). The Susitna project was finally cancelled by the state government in 1985. NAWAPA  The North America Water and Power Alliance (NAWAPA) was conceived in the early 1950s (a time when most bad Alaska megaproject ideas were born) by engineers from Los Angeles. The plan was to somehow hook up a large-scale water pipeline and canal system from northwestern-most reaches of North America (Alaska, the Yukon, and British Columbia) to the southwestern USA and even as far as Texas. NAWAPA was, among other things, supposed to make a whole lot of water run uphill, and to dam every significant river between Anchorage and Vancouver for water, power, or both. Since the NAWAPA plan called for a series of very high dams in the deep river canyons of British Columbia and southeastern Alaska, Canada would have shouldered the bulk of the project's massive environmental consequences. The likely devastation was to include, but not limited to, the destruction of most of the salmon runs in North America. Also, entirely different types of rocks and soils exist in Alaska/B.C. than in the southwestern USA, which could result in water-mineral chemical reactions rendering the water toxic by the time it reached its arid destination. So if all of that Alaska/B.C. water had traveled to somewhere like Arizona, in all likelihood it would not have been safe to drink, or to water crops or livestock with. The evaporation losses expected along the water's 2000+ mile journey would have made this problem even worse. The NAWAPA boosters spoke beautiful visions of creating giant new inland seas of fresh water, with proposed names such as Lake Nevada, and Lake Geneva in Arizona. Anyone who wants find out about the water quality of large artificial reservoirs in the desert southwest should visit Lake Mead or the Salton Sea. By the mid-1960s, NAWAPA was the subject of exploratory discussions between the Canadian government and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk. First proposed as an overland system, the plan was later revised as a large pipe submerged below the Pacific Ocean, along the West Coast shoreline. Described as the "cheap option", the underwater pipeline was estimated back in the 1970s to cost $150 billion for a 2,000 mile-lone pipeline to deliver water to southern California. By the early 1980s, anti-NAWAPA sentiment in B.C. had greatly increased, so the project's promoters began to scale the project down, resorting to the offshore pipeline idea. The project was mostly dead by the mid-1980s, because by then even NAWAPA's most rabid supporters couldn't figure out how to pay for it. An article by Sam Howe Verhovek of the Los Angeles Times, entitled "Building fancy: State's leaders continue tradition of elaborate development ideas" appeared in the Sunday, August 13, 2006 Anchorage Daily News. Verhovek quoted the 86-year old Hickel as still pushing the late-NAWAPA pipeline plan: Someday, they'll build it," he said, holding up an old promotion poster for his "Alaska-California Sub-Oceanic Fresh Water Transport System" ... "I may be dead by then," added Hickel, "but they'll build it". Asked how much Angelenos would have to pay for the water, he replied: "Depends how thirsty they are." Hydrogen Bombs (Imagined and Real) In the late 1950s, the famed physicist Edward Teller, most famous for helping the U.S. develop the hydrogen (nuclear fusion) or thermonuclear bomb, came up with a plan to detonate some of the biggest nuclear bombs of the U.S. arsenal on the Chukchi Sea coast of northwestern Alaska. Originally scheduled for the summer of 1959, the Project Chariot nuclear excavation proposal was part of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)'s Operation Plowshare, and was never carried out. Five separate thermonuclear fusion bombs (two 200-kiloton and three 20-kiloton explosives) were to be set off on a coastal site 125 miles north of the Arctic Circle, to blast out a new deepwater harbor in between the communities of Kivalina and Point Hope. Despite the fact that no one at the time could demonstrate the need of a deep-water port in this area, the AEC had the audacity to justify an expensive adventure in "geographical engineering". Although the explosions were expected to hurl radioactive fallout as high as 30,000 feet, Teller and other AEC scientists claimed that there would no human or environmental impacts whatsoever. Teller, during his commencement speech at the 1959 graduation of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said that ".anything new that is big needs big people in order to get going. and big people are found in big states". Present-day obesity statistics for Alaska notwithstanding, he even promised that he could blast a harbor shaped like a polar bear. Around the same time, the editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, George Sundborg, wrote "we think the holding of a huge nuclear blast in Alaska would be a fitting overture to the new era which is opening for our state, " and that "Alaskans are being given the opportunity to 'vote' on the matter though their Chambers of Commerce." The state Chamber of Commerce soon endorsed the project, and Robert Atwood, the editor-publisher of the Anchorage Daily Times, was also a strong supporter. The Alaska House of Representatives passed a resolution in support of the project on March 9, 1959. Opposition to Project Chariot soon involved national environmental groups such as the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society. In the beginning, relatively little opposition came from within Alaska itself, though several political leaders and local Native communities started voicing concerns as early as 1959. A handful of concerned Alaskans formed the advocacy group the Committee for the Study of Atomic Testing in Alaska in January of that year. This group sent the AEC a list of detailed questions in mid-February 1959. State and national opposition to Chariot picked up in 1961. Several University of Alaska scientists were even fired for speaking out against Project Chariot, as described in the 1994 book The Firecracker Boys by Dan O'Neill. In August 1962, nuclear debris from Nevada bomb tests was buried on the site as part of a "drinking water contamination experiment". The Project Chariot site was finally given up in 1963, by which time the AEC had spent $3 million on it. After the project's cancellation, the Anchorage Daily Times had a racist editorial about how the frontiers of atomic science had been overrun by Eskimos. Later, three actual H-bomb tests were conducted on Amchitka Island in the Aleutians: the 80-kilotton Long Shot (1965), the one-megaton Milrow (1969), and the 5.2-megaton Cannikin (1971), the largest single underground blast in U.S. history. The island was studied by the Department of Defense as a possible nuclear weapons testing site as early as 1951. The reasons for site being selected included its proximity to Kamchatka Peninsula, where U.S. officials suspected that the USSR could 'secretly' explode underground nuclear bombs disguised by the region's seismic and volcanic activity. After these three blasts, all nuclear testing on Amchitka were halted by the government over concerns about North Pacific fisheries. Protests against the Cannikin test electrified the anti-nuclear and environmental movements, and even led to formation of the Greenpeace organization in Vancouver. The Cannikin test even inspired the plot of the 1972 movie Godzilla vs. Megalon, one of the lower grade of the Japanese Godzilla movie series. In the story, the undersea civilization Seatopia experiences major earthquakes because of the Cannikin explosion. Naturally upset by this, they unleash their civilization's protector, the insect monster Megalon to destroy the human race. Godzilla then comes to the rescue and defeats Megalon to save humanity. Health problems to workers involved in the three Amchitka tests are still being resolved, and the Department of Energy (DOE) returned to the Amchikta site in 2001 to remove environmental contamination. Drilling mud pits were stabilized by mixing with clean soil, covering with a polyester membrane, topped with soil and re-seeded. Concerns have been expressed that new fissures may be opening underground, allowing radioactive materials to leak into the ocean. A 1996 Greenpeace study found that Cannikin was leaking both plutonium and americium into the environment, though a 2004 study by the University of Alaska Fairbanks reported that there were no indications of any radioactive leakage. Similar findings are reported by a 2006 study, which found that levels of plutonium were "were very small and not significant biologically". The DOE continues to monitor the site as part of its ongoing remediation program. This is expected to continue until 2025, after which the site is intended to become a restricted access wildlife preserve. The Denali Dome City At the end of the 1970s, a plan was in the works to erect a domed "indoor city" in what is now Denali State Park. The huge dome structure was to be made of Teflon plastic, sited in the Peters Hills area just south of the Tokositna River, and serve as a gateway to the south side of Denali National Park. Underneath the dome were to be lodging, a myriad of services, and a visitor center, all part of a year round destination complete with a ski resort, small airport, campgrounds and trails. This proposal was pushed by Mike Gravel, then a Democrat representing Alaska in the U.S. Senate. In May 1979, the state legislature set up the Tokositna Special Committee to conduct a feasibility study. Disadvantages cited by this study included sensitive environmental areas, conflict with existing mining claims, and untested Teflon dome technology. Other "northern dome city" proposals dating back to the 1950s and 60s included the Canadian government's plan to build an indoor domed city at Frobisher Bay (Iqualut) on Baffin Island, and similar proposals in the USSR. Bering Strait Crossing Of the five unrealized Alaska megaprojects described here, the Bering Strait Crossing, either in the form of a bridge or a tunnel, is the one idea which is most likely to be resurrected in the future. Despite the ever-increasing trade between Asia and North America, large cargo ships can still do the same job for a lot less expense. A railroad tunnel under the Bering Strait, connecting Alaska's Seward Peninsula to Chukotka in the Russian Far East, was proposed as long ago as the 1899 Harriman Expedition. In addition, bridge proposals for the Bering Strait are still being talked about, such as the Intercontinental Peace Bridge (www.beringstraitcrossing.com).  For a truly inter-continental land transportation link, thousands of miles of new connecting roads and railroads that would need to be constructed on both the Asian and North American sides, and would cost in the tens of billions of dollars. Wally Hickel said recently that a 90-km (55-mile) rail and highway tunnel under the strait would cost $30 billion. For Hickel, being a wealthy American, of course the tunnel would have to accommodate automobile traffic. But can you imagine the Alaska State Troopers putting up with a bunch of Chinese and Russian-licensed vehicles on our state highway system? All of these past megaprojects could be more accurately called megaproposals, because they never actually got beyond the proposal stage. In other words, they were a lot of talk, and not a single one of them were carried out. And in each case, critics of these projects were labeled as being "anti-development" or "anti-progress". Sound familiar? Brian Yanity is a graduate student at UAA, activist and freelance writer. He resides in an undisclosed location in Southcentral Alaska, and can be reached at byanity@insurgent49.com. |

|